Over the years, we’ve asked more than 1,000 workplace managers not only how they count people in their space, but the challenges they’ve faced with their current solution.

We compiled some of the most interesting and common challenges below, in large part to help you realize you’re not alone. People counting is hard — even when you use certain technologies to simplify it.

Editor’s note: We’ve anonymized the stories — because privacy matters to us.

“Where is everybody?”

One night while closing, a library manager was startled to discover that his people-count platform counted 2,000 people in the building.

2,000?

The library never sees 2,000 people at one time, let alone at closing time. Where were these 2,000 people? The library was empty. You could hear a pin drop.

At the time, the library used camera-driven tech to know how many people came into the building (they’ve since switched to Density).

When the manager logged into his security camera system, he didn’t see 2,000 people milling around. He saw one stray dog running wild in and out of the library vestibule. The cameras couldn’t differentiate between humans and a dog. So, they counted the dog as a new visitor over and over again.

This wasn’t just an unexpected moment — it could have had disastrous implications.

Public libraries get funded by proving people count. They can face legal issues if they provide false data. If the manager hadn’t discovered the dog, he and his understaffed team might have had to invest countless hours months later to find out why one night they had a random spike in visitors.

“Big Brother is watching you.”

A couple of years ago, the head of facilities at one of the most recognizable tech companies on the planet bought desk-level sensors for her offices.

Yes, these sensors can help you understand how often people sit at specific workstations. But they’re not the most discreet devices.

That’s why the day after the company installed the desk sensors, employees ripped them out — they feared their employer was tracking them.

Funny? Yes. But it’s also indicative of a larger issue — the balance between privacy and data. Employers could use desk sensors to monitor the work habits of individual employees. This could negatively impact employee morale and workplace culture.

The question is, can employee privacy and people counting technology can coexist? We think so.

“Why does it have to be so complicated?”

How do you monitor the use of 1,000 conference rooms across the globe?

It was a combination of Google Calendar and a custom-built dashboard made during an internal hackathon for one iconic company.

But this custom solution delivered incomplete data in a dashboard virtually no one could use.

Google Calendar couldn’t tell them how many people actually attended a meeting. It only recorded that a meeting was booked for a specific time, with an X-number of people on the invitee list.

Ten people could have been invited to a meeting. But if no one showed up, Google still registered it as a 10-person meeting.

And the custom-built dashboard was so complicated that the workplace team couldn’t log in on their own. They had to ask an engineer to pull reports for them.

The custom-built dashboard was so complicated that the workplace team couldn’t log in on their own.

Two Python engineers spent their entire workdays maintaining the dashboard. A Python engineer’s average salary is more than $125,000 (1), meaning it cost this company around $300,000 every year to run an inefficient dashboard.

“Turn and face the strange ch-ch-changes.”

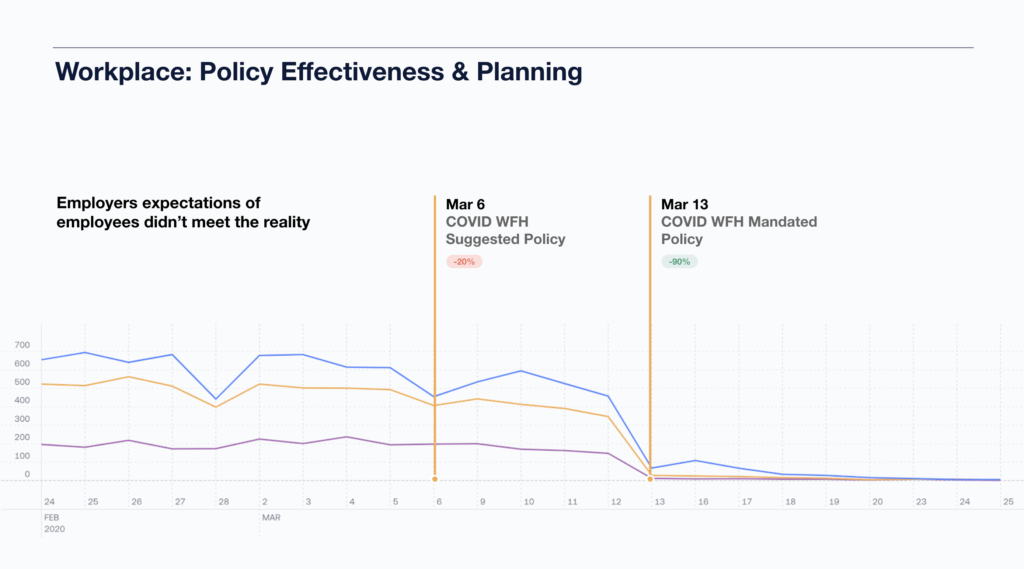

Many companies we’ve talked with over the past year had an office-first culture before the pandemic.

Now, it’s not so cut and dry. The CEO of one office-first tech company we talked with admitted his team is a lot more productive working from home than he would have once assumed.

This has him rethinking how his team uses and measures space. Before COVID-19, this company measured space using headcount and square-feet-per-employee. Now they’re left wondering if their only option for knowing how to manage space is to make educated guesses. (Spoiler: it’s not).

“I trusted you, loved you, and you betrayed me!”

A few companies we’ve talked with already use sensor technology for people count. But they felt they still needed to manually validate that data manually.

They had reason not to trust their sensor data (full disclosure, they weren’t using Density sensors at the time). One workplace manager said his sensors were triggered by a specific type of lighting. Another manager said that when a person walked by a glass office front, the office sensor thought a person entered the space.

These miscalculations create distrust, leaving companies no choice but to manually validate the data.

You shouldn’t have to do something twice. That’s not an effective way to run a company. At Density, we’re proud of the 98%+ accuracy of our Entry sensor.

“Badges? We don’t need no stinkin’ badges!”

Many companies we talk with use badge data to track occupancy, mostly because they already have badge systems in place. It’s convenient.

But, the data is also incomplete and a pain to access. A Fortune 500 company we now work with walked through all the ways badge data caused more headaches than helped.

For context, they (like most companies) only employed badge-in access at the front entrance. Employees didn’t have to badge-out to leave the building. They didn’t have to badge into or out of conference rooms, micro-kitchens, or soft-seating areas.

Whenever the workplace team wanted badge-swipe data, they had to go through their security team, who would scrub the data of personally identifiable information (PII) first. By the time the workplace team got the data, it was weeks or months in arrears and didn’t paint an accurate occupancy picture.

“It’s great to get badge-in data, but if it’s a salesperson going in for a Coke or quick meeting, it’s not really telling us how our space is used.” — Fortune 500 Workplace Manager.

It also didn’t help that the occupancy data of tens of millions of square feet were compiled into spreadsheets.

We know some folks love spreadsheets. But that’s a lot of tables to sift through.

“You’re not alone.”

It’s never been easy counting the number of people in your workspace throughout the day — let alone understanding how they use it.

It’s even harder now, when flexible work has become the new standard. Eight-hour work shifts and dedicated desks are a thing of the past. Employees come to the office a couple of days a week, for just a few hours of the day. When they’re in the office, they sit at a desk, reserve a conference room, and relax on soft-seating.

The pandemic shook the Etch A Sketch and we’re all starting over. New baselines need to be created.

But just because something’s hard doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. Real estate is your second highest line item on your P&L sheet. And in this new workplace, you probably have no idea how it’s used. The pandemic shook the Etch A Sketch and we’re all starting over. New baselines need to be created.

The good news is you’re not alone. Your colleagues around the globe face the same challenges you do — before, during, and after the pandemic. And tools like Density are making people counting and space analytics easier and more useful than ever before.